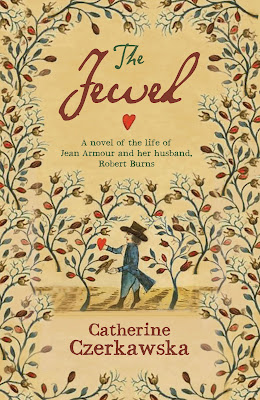

Happy birthday to Robert Burns who was born on this day, here in Ayrshire in 1759. I knew little about him when we moved up here in the early sixties, but I quickly became a fan. Over the years, I've written a radio play and then a stage play about him. But my biggest project was The Jewel, a novel about the poet's wife, Jean Armour, and a companion anthology called For Jean, Poems, Songs and Letters by Robert Burns for his wife. He called her The Jewel of them all, and so she was. But although the novel is a third person story (he said, she said) it is nevertheless very much told from Jean's point of view, So of course, I too began to see the poet from his wife's point of view.

And was equally charmed by him.

Whenever I've done book events or talks about the novel, somebody in the audience - usually a woman - has asked me what I thought about him, and I've always had to confess that I reckon in Jean's shoes, I'd have fallen for him too. Hook, line and sinker.

One of his most attractive qualities must have been his sense of humour. He made people laugh. He made women laugh. He genuinely seemed to like women, young, old and every age in between - which for a man of his time was a fairly rare quality. If he had to fall in love to write a love poem - as he himself admitted - he also had many genuine friendships with women throughout his too short life. He had his faults, but my goodness he must have been attractive.

Anyway - hope you've got your haggis and neeps and tatties for tonight. (I love Burns, but haggis, not so much!) - and perhaps a wee dram as well.

Here's my very favourite version of Rab's song about himself, from the late, wonderful and much missed Andy M Stewart: Rantin Rovin Robin.

There was a lad was born in Kyle,

But whatna day o' whatna style,

I doubt it's hardly worth the while

To be sae nice wi' Robin.

Chorus - Robin was a rovin' boy,

Rantin', rovin', rantin', rovin',

Robin was a rovin' boy,

Rantin', rovin', Robin!

Our monarch's hindmost year but ane

Was five-and-twenty days begun

'Twas then a blast o' Janwar' win'

Blew hansel in on Robin.

Robin was etc

The gossip keekit in his loof,

Quo' scho, "Wha lives will see the proof,

This waly boy will be nae coof:

I think we'll ca' him Robin."

Robin was etc

"He'll hae misfortunes great an' sma',

But aye a heart aboon them a',

He'll be a credit till us a'-

We'll a' be proud o' Robin."

Robin was, etc

"But sure as three times three mak nine,

I see by ilka score and line,

This chap will dearly like our kin,

So leeze me on thee! Robin."

Robin was, etc

"Guid faith," quo', scho, "I doubt you gar

The bonie lasses lie aspar;

But twenty fauts ye may hae waur

So blessins on thee! Robin."

Robin was, etc