|

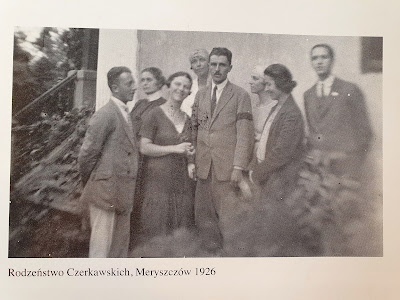

| The Czerkawski siblings, Meryszczow, 1926 |

As I said towards the end of

my last blog post, I'm in the middle of researching my Polish grandfather's life story, for a new book. We're in the middle of a pandemic and enduring the hideous culmination of a Brexit that a large majority of people in Scotland (and many in England) didn't vote for and loathe more and more, the deeper Westminster drags us into it.

All of which is keeping me awake at night.

The photograph above is in the book about the Kossak family that I also mentioned in that last post and that had been sitting on my bookshelves for some time. Wanda Czerkawska - the shyly smiling lady facing the camera - was going to marry artist Karol Kossak in 1927, so her story would become part of the much more famous

Kossak family story. Wanda was born in 1898, so she was six years older than my grandfather, and 28 when this picture was taken. They must have believed that she would become an old maid, at a time when women especially tended to marry young. The book is in Polish. My command of that language is very limited, so I could do little more than skim through it, although a friend translated the chapter on Wanda's family for me. I thought I had looked at all the pictures, but when I was casually leafing through it a few weeks ago, the photograph above leapt out at me. I'm not sure why I hadn't noticed it, but perhaps it was because the book was still new and shiny, I had simply missed the page.

It excited and moved me.

I have only two other photographs of my grandfather. One is a small head and shoulders snapshot and the other is with my grandmother and my father as a young child. His hair is in a bob, and he's wearing a smock, as boy children did in those days. But until I saw this new picture, I had no group images of the siblings of the family and none so early.

It's intriguing, that photograph.

|

| My grandfather |

Firstly there's the focus on my grandfather, Wladyslaw Czerkawski, in the middle. He was more handsome than that in other pictures, but here, he is the main figure in the picture, with the rest of the family slightly out of focus, grouped around him. He looks solemn and thin and under a certain amount of stress. And he's wearing a black armband. I'm fairly certain that he is wearing it for his mother, Anna, who had died in 1925. This had left Wladyslaw central to the family in all kinds of ways. His widowed mother had made a second marriage, one of which, for various reasons that are becoming clearer to me, the family disapproved intensely, and which seems to have been less than happy. There was a child of that marriage, Danuta Hanakowska, born in 1920, and Wladyslaw must have known that her care and upbringing would be left to him and his young wife, again for reasons that are becoming clearer to me. I'd been wondering about the starched lady at the back of the picture, the one turning away from the camera as though she doesn't quite belong. But of course she would have been Danuta's nurse.

Of the others in the picture, the lady in profile with thick, dark, bushy hair (hair that she passed on to me) is my grandmother, Lucja. She was only 20, though she looks older, and the little bump she is showing would have been my father, who would be born in May of that year. At the back, between my grandfather and grandmother, you can see the profile of a pretty young woman, fashionably dressed in white. That would be Ludmila, or Ludka, the beautiful, spoilt baby of the family. I remember seeing a picture of her among Wanda's possessions, when I was in Poland in the 1970s, dressed in silk lounging pyjamas and sporting a cigarette in an elegant holder. It was, of course, difficult to copy photographs back then, but if anyone out there still has them, I'd be delighted to have copies of them. I think they may be with the Kossak relatives in Sweden, with whom, sadly, I lost touch.

I don't know who the others are: the lady with the cloche hat at the back ('she looks like you' says a friend) or the tall, good looking man on the right, or the slightly self satisfied man on the left. But since the caption says 'Czerkawski siblings' they may be Wladyslaw's reckless elder brothers, Zbigniew and Boguslaw. Zbigniew died of consumption in 1932, while Boguslaw (Bogdan) was killed during the war in 1943.

The picture was taken at an estate called Meryszczow, but at this time, Wladyslaw and Lucja were living at another estate, some kilometres away, called Dziedzilow, which is where my father was born, so they must have been there because of the death in the family and its consequences. Wladyslaw would have fallen heir to Meryszczow as well, had war not intervened.

Old photographs are always mysterious moments in time, caught like fossils in amber. This has a momentous quality to it, because it was a turning point for all of them in more ways than one.

I look at this picture and see that none of them had an inkling of what was about to happen, a little more than a decade later. Only two of them would survive, three if you count the bump, and of those, only two would go on to have a fulfilling and happy life after earlier turmoil

Which leads me back to thinking about the uncertain times we live in now. We're here at what feels - not like the culmination of something, although it is - but at the start of something worse. Unless Scotland can find a way of extricating itself from the hard right Eton Mess that has infiltrated the Conservative party (never my party of choice, but - at other times - never ever as mad and bad as they seem now) we are in for some miserable years. The notion of a sovereign and thriving UK is proving to be the jingoistic mirage we always suspected it was. Personally speaking, if we were younger, we may even have left by now, and taken our chances in mainland Europe or Ireland, much as many of those in this picture might have been better to move away, head west, possibly to America, where they would at least have stood a chance of survival.

But we don't, do we? We have loyalties and allegiances, homes and friendships. And in our case, we have a Scottish government with a certain level of competence and care and the possibility of independence. So we hang on and hope for the best, even as we fear the worst.

These were people who knew all about the reality of difficult borderlands, where life could be short and violence was never very far away. Maybe like people living on the edge of a volcano, they thought it wouldn't happen to them. Maybe, like my friends and relatives here who keep shrugging and telling me that nothing will or can be as bad as all that, they thought it better to sit it out. Maybe they'll be right, although this small group of people were wrong.

Who can say? All I do know is that as a writer of historical fiction and non-fiction, I've learned a great deal over the past few years, lessons I would rather have avoided. I've often found myself wondering what it would have been like to live at a time and in a place where things had begun to fall apart around you. What would it have been like to try to maintain your footing, and a certain moral compass, amid those shifting sands.

We read books or watch movies about Nazi Germany and we think 'Why didn't people do something?'

We read about the dreadful fate of the Jewish people, and we think 'Why didn't they see the signs? Why didn't they move away while they still could?'

We look at these people in the picture who must surely have had some small inkling of impending doom.

Well, maybe they didn't. Whoever does? Whoever really believes that things will fall apart? That human beings will be careless and cruel?

I look at my grandfather's face, and I think that of all of them, he was perhaps the only one with any kind of prescience. But in uncertain times, we cling to the hope that things will and must get better.

Sometimes, they get much worse first.

|

| Julian, Wladyslaw and Lucja |