|

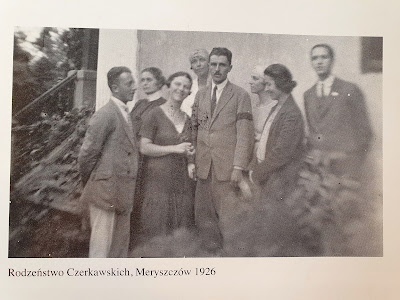

| Michael James Flynn in the middle, with the moustache and waistcoat, seated next to the man with the tar bucket. |

Most writers, whether of fiction or non-fiction (and I do both) will tell you that we become so absorbed in our subject matter that we feel as though the people we're writing about are not just real - as they often are - but alive. Sometimes that sense of reality even rubs off onto our nearest and dearest. When I was researching and writing a novel called The Jewel, about poet Robert Burns's wife, Jean Armour, back in 2015, I had talked about her so much that my husband swore that he saw her one night, walking through the door between our bedroom and my office - a woman in old fashioned dress, with something like a mob cap on her head.

My tale for today is quite different, very personal and not nearly so fleeting.

In 2018, I had been deep into research for a new book, about a murder in my Leeds Irish family. The book, called A Proper Person to be Detained, would be published in 2019 by Contraband. On Christmas Day, in 1881, my nana's uncle John Manley had been stabbed in the street by one John Ross and died where he fell. The two men had been casual friends. John Manley had refused to fight, but Ross was angry and drunk and found a tobacco cutting knife in his pocket. The murderer fled, to be apprehended a few weeks later. He was tried and sentenced to death, but the sentence was later commuted to hard labour, a mercy that I felt was probably justified.

In writing the book, I explored the situation of this poor Irish migrant family, whose parents had fled famine, only - like so many - to be abused and exploited in the industrial cities of England and Scotland. Researching the book also gave me the opportunity to find out more about my great grandfather, Michael James Flynn from Ballinlough, County Roscommon. (He went by both christian names.) He married my great grandmother, the murdered man's sister, Mary, already a widow with children, in St Patrick's Church, Leeds, in 1888. The Manley family had come from Ballyhaunis in Mayo, but the two villages are only five miles apart, so there may have been family associations. At that time, he was a paviour's labourer, but later, he would describe himself as a paviour. He built roads and pavements.

From the accounts of those who knew him, he was a good, kind, generous man who managed to transform the fortunes of the family. The household into which I was born, more than sixty years later, was by no means wealthy. It was still a working class household, but it was warm, clean and comfortable. Nobody went hungry. My nana remembered Michael as the most generous of fathers. If he was wearing a winter coat and he saw a beggar on the street, he was quite likely to hand it over to the more needy man, to the occasional frustration of his wife.

So what about my Hallowe'en story?

It happened in a supermarket car-park of all places. Not long after I had finished the book. It was one of those chilly, misty mornings, with a low sun shining in my eyes as I walked from my parked car to the door of the building. It was early and the car-park was fairly empty. A man walked out of the mist and the sunlight and headed straight for me. I had just crossed the narrow roadway leading into the parking spaces, but halted as he approached. I remember that he put a gentle hand on my elbow and encouraged me to step up onto the pavement. 'Take care, madam,' he said. He was Irish. Not Northern Irish, as so many visitors to this part of south west Scotland, but a soft southern Irish voice.

'I was wondering,' he said, 'if you might be able to give me something to get myself a bit of breakfast.' He glanced back towards the supermarket doorway. 'They've all been ignoring me,' he said.

I looked him up and down. He was covered in grey-white dust - it looked like plaster dust - from head to toe. He wasn't dirty or drunk. Just dusty. He wore boots and they too were dusty. He looked like a working man, a labourer.

I didn't hesitate. I looked in my purse, found a five pound note, and gave it to him. I don't carry much cash these days and it was all I had. He thanked me. 'God bless you,' he said. 'God bless you!' And off he went. I watched him walk into the misty winter sunshine, as he headed towards the steps leading up into the town. I never saw him go up the steps.

I had one of those sudden intimations of something odd. Not frightening at all, you understand, but uncanny. And strangely uplifting. I headed for the supermarket, but had to find a seat and sit down for a moment or two. I felt quite shaky. It struck me that I have seldom, if ever, seen or heard an Irish labourer travelling alone in this part of the world. Ulster yes, but Irish? Tattie howkers used to come, but they seldom do now, and besides, it wasn't that time of year.

I've never met one since.

I can see him now, feel his gentle hand on my elbow, his warm 'God bless you!'

All through my shopping, and all the way home, I thought about my kind, generous, much loved great grandfather, a man I had never known, but who was very much on my mind. Of course the sceptics will easily explain it away. And in a strict sense, it is perfectly explicable. Isn't it?

But I know what I saw. And I know what I felt. And it's an encounter that I still treasure.

What do you think?

PS, If you would like to read a made-up supernatural tale, you'll find my strange little novella Rewilding free on Kindle, from 31st October, for five days.